Jaro Picks: Author And Illustrator Monique Duncan Is Bringing Multicultural Stories To Children

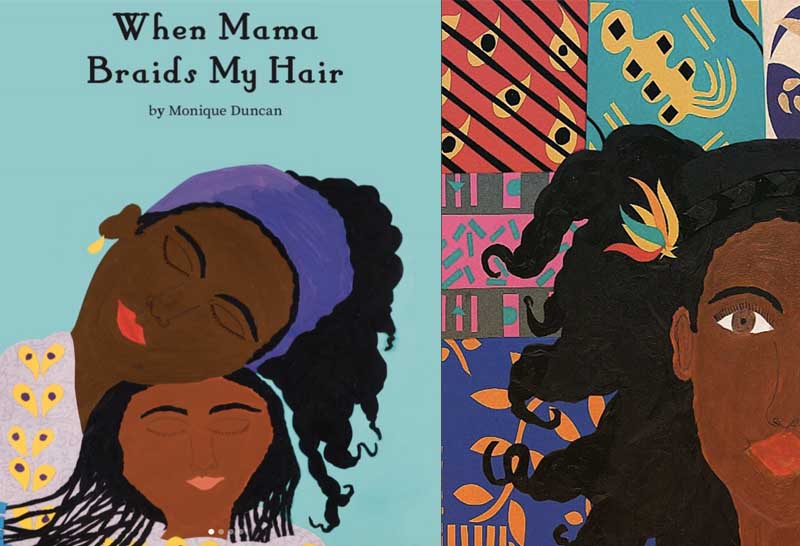

When Mama Braids My Hair by Monique Duncan

How do you juggle your passion with your full-time career? For children’s book author and illustrator Monique Duncan, the two worlds are deeply connected. We spoke with Duncan, a rousing teacher and founder of Sweet Pea Books, to learn more about how she merges her love for teaching young children with her passion for bringing culturally diverse stories to the forefront.

As a seasoned elementary school teacher in New York City, Duncan personally understands the urgency for more diverse children’s books, and the impact that representation and inclusion has on our youth. Thus, when she founded her publishing company Sweet Pea Books back in 2009, Duncan embarked on a devoted journey to create multicultural books that her own students could identify with. In When Mama Braids My Hair, she beautifully captures a bonding moment between mother and child that many young African-American girls experience, informing readers on the history and tradition of African hair braiding. Overall, Duncan’s stories offer young readers an opportunity to interact with literature in a way that is empowering and self-actualizing.

Speaking to us with a passion out of this world, Duncan shares the challenges and advantages of being a self-published writer, her illustration process, heartwarming stories from the children she teaches and inspires daily, and what’s next on the horizon for the budding author.

What makes your publishing company, Sweet Pea Books, stand out among others?

My company is making sure that children are not only seeing themselves in books, but ensuring that their stories are being told. I want children to feel like they can relate to the stories that I tell. I want them to feel that their stories are connected to who they are, connected to their identity. So while I know that there’s been a push in the last few years to level the playing field in terms of diversity in children’s books, there’s still a huge disparity, and my niche is really about focusing on identity–but also connecting, helping children connect who they are to where they came from as well, and really starting to spark some conversations around those connections.

For example, the books that I’m writing now are really focused on helping children see that they’re connected in a different way. My current book that I just finished, When Mama Braids My Hair, is teaching them that their hair styles that they’re wearing are not just intricate styles that look nice, but they’re actually connected to the continent, and that’s a huge part of who they are.

When writing When Mama Braids My Hair, was there any particular interaction with a child that helped you make the connection between hair styles and history?

It was actually inspired by a number of interactions. I’ve worked in New York City for over 14 years, and I worked in an all-girls school for a while in the South Bronx. One interaction in particular that I remember is of a student who, whenever she had her hair done, if she had extensions or something like that, you could tell that she felt that she looked more beautiful in her mind. She would come up to me and say, “Oh Ms. Duncan, do you like my hair? Look at me!” And I would tell her specifically that she looked beautiful with her hair braided, and she looked beautiful with her hair in pigtails, just so that she wouldn’t only identify with, “I look beautiful in this one way.” I wanted to give children other opportunities to see, and I wanted us to define what beauty meant for ourselves, and not what her peers or society would say it is.

There definitely have been a lot of conversations in my teaching that have come up with color and ideas around beauty based on the color of your skin. There’s been a lot of discussions around impressionable children, and the messages that are blatant and the ones that are not articulated. They’re still picking up on these messages about what is considered beautiful, what’s instilling pride in them. I wanted them to be able to see that we’re much more than our appearance, and there are many different ways to describe beauty.

What are some of the advantages and challenges that you face as both the author and illustrator of your books?

When I initially started out, I only envisioned myself writing. I do like to draw, but it definitely is a testimony for some of my students because I didn’t go to school to be an illustrator, so I automatically downplayed what I could do. That was a big mistake, because if I continued to think that way, I probably wouldn’t have the books that I have published today.

One of my students actually told me, “You could draw the pictures.” It took a child to tell me I could draw the pictures, and I was like, “Maybe I can.” I started drawing and dabbling, and of course, my students are the toughest audience because this is for them, and they were the ones who encouraged me. My first challenge was believing that I could do both.

The other piece of it was when I decided that I was going to self-publish. I originally was just going through the traditional market, sending my manuscripts to publishers. A lot of times, they’ll tell you not to send illustrations unless you are an actual artist. So there was another barrier for me in a way, where I was confronted with them taking me seriously. A friend of mine encouraged me to self-publish, and so I can’t imagine not illustrating and writing anymore. When I write, I envision what’s happening, so therefore sometimes in my process, I even start illustrating before I finish writing. It’s really married for me.

Because I self-publish, the challenges aren’t as apparent. If I were to go the traditional route, I would have to face the question of a publisher and editor liking both the manuscript and my artwork, or if they would just want to take the manuscript. Self-publishing really is a good path for me because I don’t have to worry about that. I definitely get great feedback on both, so I prefer it because I don’t have to rely on an illustrator and wait for them to draw the pictures, and see how my ideas manifest for them. I can take ownership of that and create.

The two biggest challenges to self-publish is having the capital and marketing, which would be eliminated if you went the traditional route. However, you don’t have the freedoms that you would have as a self-publisher. I hire my own editor and my own graphic designer. No one was appointed to me. What I really like about the process that I have with them is it’s really a collaborative effort, and I don’t have this case where my work is being edited and I’m not pleased. The decision making comes from both of us, but I have a heavier hand in it.

The interesting thing about it is a lot of people are self-publishing right now because [taking the traditional route] is such a competitive field. Even if your material is good, the publishers are making an investment in you. Even after a year, if you’re not selling enough books, they’re not looking at you anymore. I learned that a lot of traditionally published authors do a lot of work outside of what their publishers offer. It was enlightening and refreshing to hear that they have to really grind as well. The only positive for them is they have a huge name behind them; it’s easier for them to get into Barnes and Noble, and on these book lists. I’m not going to say it’s impossible for me, it’s just a challenge. I definitely encourage looking at both sides and doing what works best for you.

You mentioned that you receive good responses about your work. What are some memorable responses that you’ve received from a child or parent?

I wrote a book called Polka Dot Face, and it’s about a young girl who has beauty marks, and she’s being teased for these beauty marks. She goes through all of these trials to remove them, and I think that’s the innocence of a child. “Okay, I can get rid of these beauty marks if I put a mud mask on that I read about that removes pimples.” A child goes through all of these ridiculous trials to try and get rid of these marks because she’s being teased. She has to go through some of those trials and deal with those consequences in order to realize that we’re all unique in our own way, and it goes back to this idea of what is beautiful. I can define what beauty means to me, and I don’t have to accept what you’re saying about me, because I believe that I’m a beautiful person. It goes back to just having that self-love, and instilling that.

When I read that story, especially to my first grade female students, they were all over it. Kids are used to being teased; it’s just an unfortunate part of a child’s life. Being able to identify with that was something that really spoke to some children. A student said to me that because of the story that I read to her, she felt empowered in a way. It was that sentiment, and that’s exactly what I wanted the book to do. Just in a short reading, I was able to change a child’s perspective about herself and who was teasing her, and that she didn’t have to allow or accept it, because she didn’t have to believe it. That was really powerful for me, because at that young age, she was able to internalize the story, walk away, and feel empowered.

When I was reading When Mama Braids My Hair to a group of third graders, there’s a part in the story where I talk about the mother tugging, combing, and pulling the child’s hair, and when I said that, all the girls in the class made this “me too” sign. They could immediately relate to sitting between their mother’s legs and getting their hair combed. That was a really special moment for me because it was about 25 students who right there it was just like, “I can relate to this.” I can imagine the feeling that they had inside, like, “Wow, my life is depicted in a book.” That’s pretty important. These are just little examples of how I get to see that my work is doing exactly what I want it to do, and really helping children feel good about themselves, feel a sense of pride, feel empowered, and just also being able to connect.

It’s powerful when a young child can identify. I remember as a child myself, I loved to read. I really loved Corduroy as a young child. As I got older and I look back, I was like, why do I love that book so much? Maybe because Corduroy’s owner was a black girl, and I identified with that black girl because she looked like me, and I went to the laundromat with my mom. It’s just important for our stories to be told so that we can feel valued in different mediums, whether it’s literature or television, or however we’re presented, as long as we’re represented.

What’s the writing process like when creating a children’s book?

Like with any genre, there’s always some type of formula. With a children’s book, I know that basically you have to have 32 pages. When I think about that, I’m thinking about my word count. When I write, I just write and get it out. That usually will come in the revision process, but as I’ve written more books, I have in my mind that I don’t want to go over because less is more, and I’ve definitely learned the hard way for a picture book.

When you’re thinking of reading a book in one sitting, you don’t want it to be too long because I’m thinking about how long a child will be able to sit. If it’s for a specific audience, you want to think about all of those things. I visualize what’s happening as well when I’m writing. There are times when I sketch as I’m writing. Some of those sketches don’t make it, but I am inspired to do some artwork sometimes before I’m finished writing the story.

One of the things my editor really made very clear to me early on is obviously for this audience, less is more. It’s not so important as to how many words you use, it’s the type of words that you use. With a children’s book, what’s really challenging is using fewer words that are more powerful and drive your message home. Not being redundant is important in my process, and not using too many adverbs. It’s really just about making my verbs really powerful, so I think about the verbs that I use and the personification that I give objects. I read a lot of children’s books, too, and I admire different authors. I look at their language, and how they write. I get inspired from what I read as well.

Who are your favorite multicultural children’s books authors?

I love Jacqueline Woodson. She’s definitely an amazing author. She has a command on words, so I really admire her work and what she’s done in children’s books and also in the YA field. I’m also a fan of Kwame Alexander. He writes in this literary prose genre, but it’s very powerful, and I appreciate also looking at different genres of writing.

I’m a reader, and I love Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I admire her writing. She obviously is not a children’s book author by any means, but she’s a phenomenal writer. I look at the way that she expresses herself, and I’m inspired by that as well. I look at different genres, I look at different age groups for audiences, and I get inspired just with how language is being expressed.

In your illustrations, you use acrylics and collage techniques to create these vibrant illustrations. How did you discover this unique artistic style?

I started off with just using watercolor, and then I was like, I want something more vivid. So I moved to acrylic paint. Brian Collier, he’s an author/illustrator that I admire, and I really admire his process, how his pictures come to life with this collage medium. Kadir Nelson is another illustrator that I admire who does oil painting, and they’re both beautiful and vivid and bright. But I looked at these two artists who work in different mediums, and took from that in a way. While it’s not full on collage and it’s not full on acrylic, I like this idea of layers, so I merged the two mediums.

I’ll paint in acrylic first, usually the character’s faces or their bodies, then the background or different elements, and I’ll add the collage techniques. With When Mama Braids My Hair, I wanted this vivid illustration to pop out to the reader. But if the whole book is about braiding, how can I represent the braiding in a different way? I decided to actually braid the paper so that it would pop out. The face is acrylic paint, but for the hair, I braided the paper and pasted it on. I figured that would add a nice 3D element. I just started doing that and I was like, maybe this is my thing. That’s how it came together, just really admiring other people’s work and finding my own voice and my own style, and merging these different mediums to really make my artwork pop in a different way. It’s such a fun process. I may have something in mind, but once the collage part comes in, it just takes its own direction. I have an idea in mind, but when I start layering the papers on there, I follow wherever it takes me. Not everything necessarily starts out in my mind, it just evolves as I’m working.

Do you have any other upcoming projects we can look forward to?

Yes, I always do! I’m working on a book called Elephants Don’t Have Stripes. One of the things that I’ve learned is male elephants leave the herd around adolescence, and they don’t return until they’re ready to mate, which is usually around 30 years old. The male elephants, they live these solitary lives. They come back and mate, and then they leave again. When you observe elephants and you see the young ones, they’re usually in the middle of the mothers or the larger elephants. You see them kind of lost in the middle. So I decided to make my main character a male elephant who has just left the herd and sees the savanna with new eyes.

Now that he’s experiencing the savanna, he takes notice of all these different animals, and they’re all so beautiful. He starts to compare himself to these animals, and he starts to wish and beg to look like them. He gets his wishes, but they come with some grave consequences. Again, he has to learn this idea of I’m unique, I’m special, I’m beautiful the way I am. It’s a fun story for kids, but it also has a powerful message of self-acceptance.

I have another story, more of a poem, that’s been inspired by ideas of identity again. Who am I in this world? It’s interesting because working with a number of African American students, when we start to talk about culture or identity, a lot of them are just saying, “Oh, I’m black,” and that’s it. I find that my Caribbean students are able to say, “I’m Jamaican,” or I’m this or I’m that, and I found that they have a deeper understanding of who they are culturally. I wanted to do something to bridge that gap, kind of like what I did with When Mama Braids My Hair too, because I’m making that connection that these hair styles originated in Africa.

This poem that I wrote is about identity, and I intend on making a picture book. It’s an older voice that is answering the call of a young child asking, “Who am I, who am I?” The older voice is basically telling them who they are based on lineage, based on just what we’ve overcome, and so the idea is to not only instill a sense of pride, but also to instill a healthy curiosity for you to figure it out. Don’t just accept the title or the label that you’ve been given, but really dig into who are you in this world.

What I want to help children understand is that it’s really important to have a deep understanding of who you are as a person. It’s a journey. You’re not going to get all the answers right away, but if you start on that process of trying to discover who you are and are able to really cling and own some parts of yourself, things may be a little smoother for you. You’ll feel a sense of empowerment and pride. When you’re so lost and don’t know who you are, it’s so easy for you to just get wrapped up in different things that may not be the most supportive for you. So a lot of my books are really trying to just send a message of being happy with who you are, and being open to discovering who you are as well, because you might be surprised when you learn a little bit more about yourself.

I think your stories could benefit adults as well.

I agree. It’s human nature to compare, but if we can start with children to instill this sense of pride in who they are at an earlier age, maybe they’ll be more confident and happier adults. I think my themes are universal, and they definitely cross age brackets. While it may be a picture book, there’s always a message or learning in there for older ages.

Monique Duncan is having her first official book signing for When Mama Braids My Hair on June 23rd at the Langston Hughes House in Harlem, NY. For more information about Duncan and to purchase her books, please visit her website.

No Comments